Coming to London

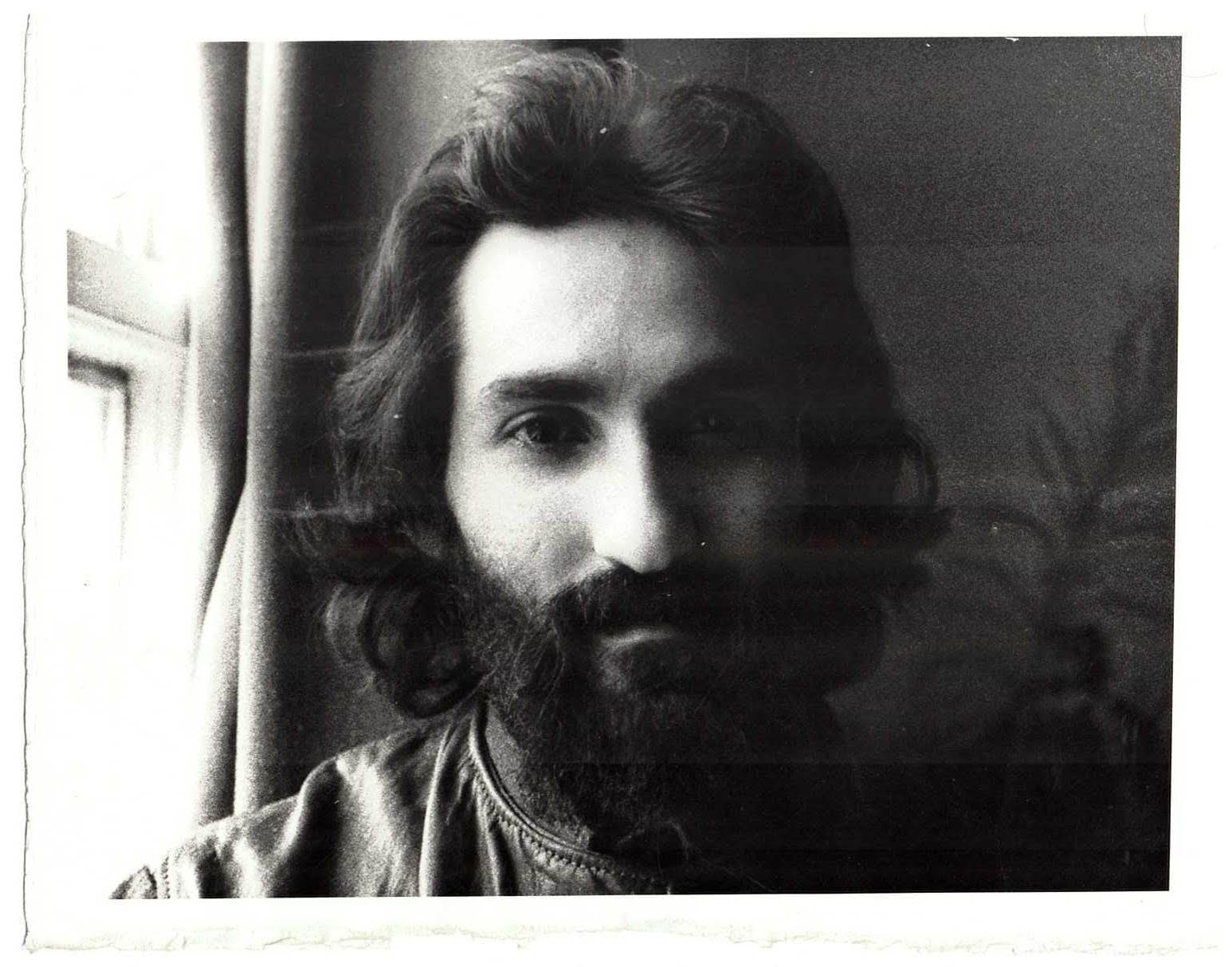

On the ship that finally bore him off to England, Mustapha shared a cabin with a part-African-part-Cherokee American sax player called Duce, who was on his way to Paris to link up with the jazz scene. Duce had been deported from Trinidad for drug offences and for walking naked down a street one night, blowing his sax.

To relieve the boredom of fourteen days at sea, confined to steerage – lower decks with two hundred males for company – he began writing a corny love letter to a girlfriend he had left behind. These letters developed into a daily journal of his thoughts, feelings, and experiences on the journey – the gambling, stealing, fights, and stowaways that constituted the stuff of life shipboard. He posted the large roll of curled pages to her on his arrival in England, and to this day, mourns its loss.

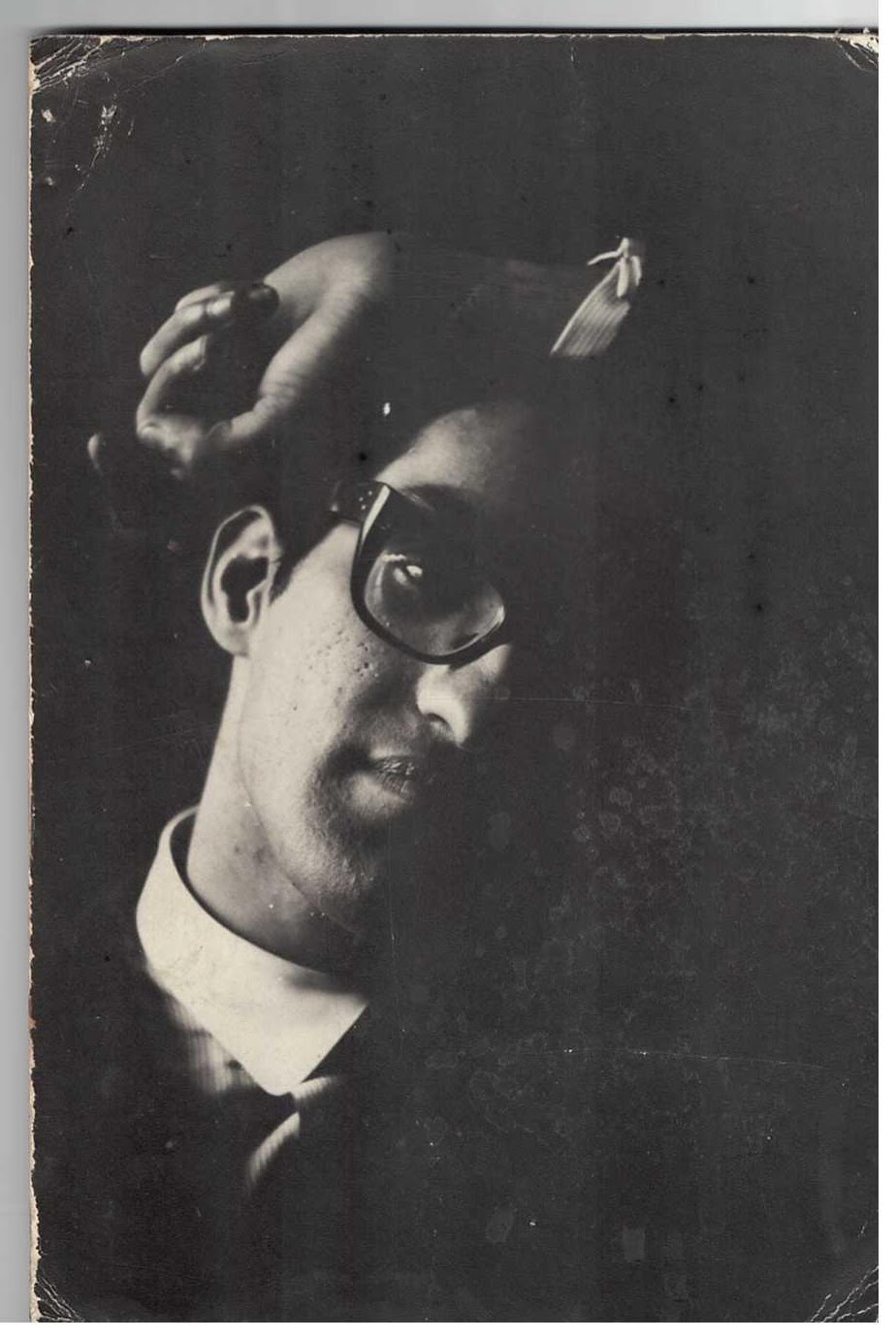

On board, Mustapha became friendly with a Dutch sailor who swapped his copy of Dylan Thomas’s ‘Under Milk Wood’ for Mustapha’s current issue of Playboy which, along with the expected erotica – in this case Japanese kimono prints – contained poems by Robert Graves. Under Milk Wood was gripping, but he also mourns the loss of the prints.

On his first morning in London, whilst staying with a friend who was running catalogue scams, he was awakened by an attractive, aristocratic Chelsea beatnik, an artist’s model who had just come out of prison for bounced cheques. She gave him a brief insight into and taste for the Bohemian life in London. When his money ran out, so did she.

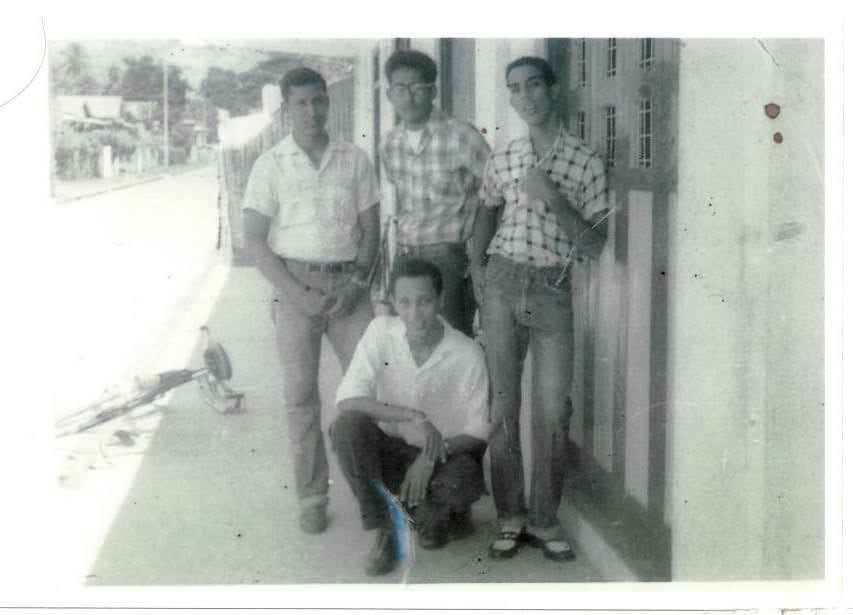

For a year Mustapha worked in England as a hospital porter, following the latest trends, films, theatre, art scenes, etc., then left for Rome with a fellow Trinidadian film director, who had heard there was work there for ‘exotic’ film extras, and sex-starved, rich women looking for gigolos.

As it turned out, the vita was not so dolce. His ‘lack of sophisticated experience’ scuppered his career as a gigolo. Mustapha and friend were soon broke, hungry, and demoralized. But they met a group of black American Actors, Musicians, and Artists, who showed them how to hustle the Roman scene, and Mustapha was hired as a curtain puller for a production of Shakespeare in Harlem – a jazzy look at black life by an iconic black American theatre figure, Langston Hughes.

Evenings, as he stood in the wings, mesmerised by the play, the idea was born that he would abandon the Hollywood idea, return to London, find an undemanding job, and settle down and write plays about West Indian life experiences.

One night in mid-dream, Mustapha panicked and opened the curtain at a time when the actors were not in position. The following night he closed it when they were meant to take a bow. He was sacked, and returned to London, where by now the spirit of the Sixties had fully arrived.

London was swinging, doors were opening or bypassed. The alternative culture whose concerns were Peace and Love had been born and was blooming. Racial intolerance and War were anathema. And the West Indian community was making its cultural and political presence felt.

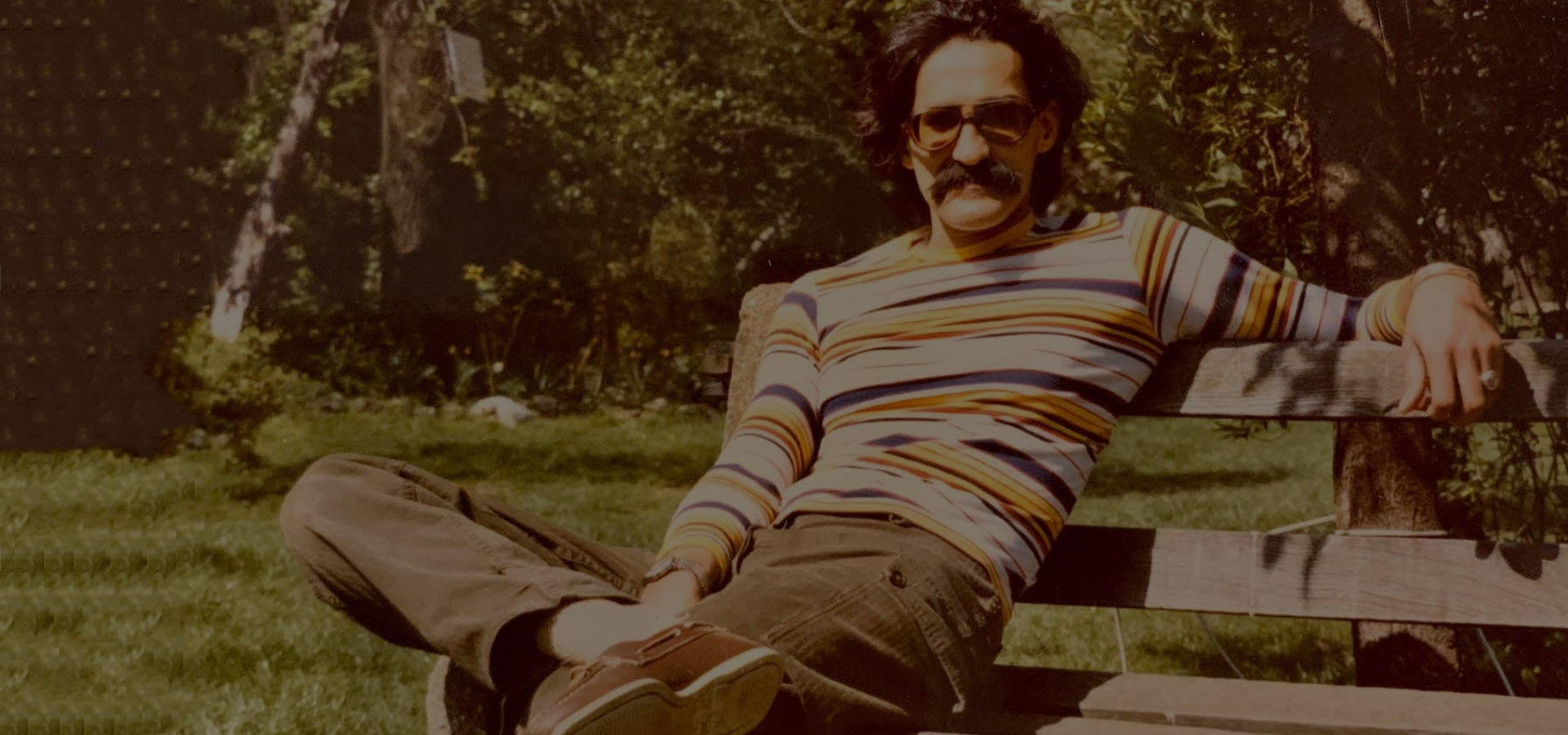

Mustapha’s own political consciousness was expanding, his anti-colonialism growing, he was hanging out on the fringes of the Black Power movement, observing and intrigued by the dramatic possibilities of the “consciousness-raising energy of conversations and confrontations,” and felt that someone had to “capture those moments, record them, write about it, tell it like it is.” And as his conception of himself as a mouthpiece of his culture grew, these words became his mantra.

He wrote three short plays set in Ladbroke Grove, reflecting the various political and social features of the West Indian community at the time, intending to show them only to his friends. But they landed in the hands of a theatre director who was looking for similar material. To Mustapha’s astonishment they were produced, reviewed, even lauded. When asked to explain his success he said that all he wanted was “for people to experience the beauty and liberation of writing in my native dialect. That was the key that opened the door, I just walked in.”