Early Life

Early Childhood

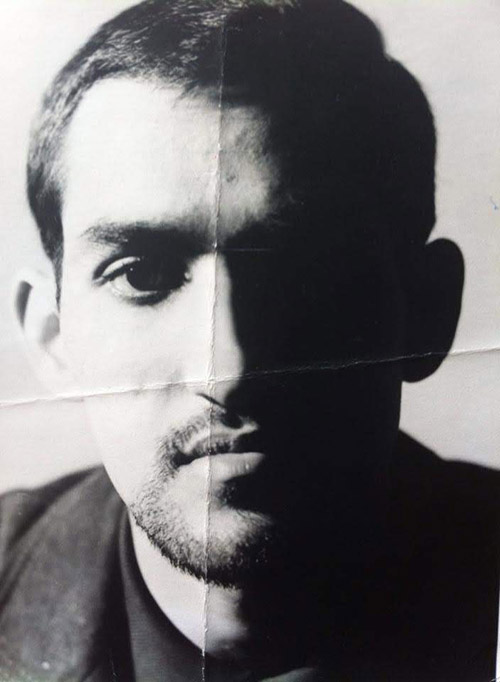

Mustapha Matura was born Noel Mathura in Trinidad in 1939, and brought up Anglican. He later changed his name — not his religion – when he emerged as a writer. “I liked the sound of it,” he explains. “It was the sixties.”

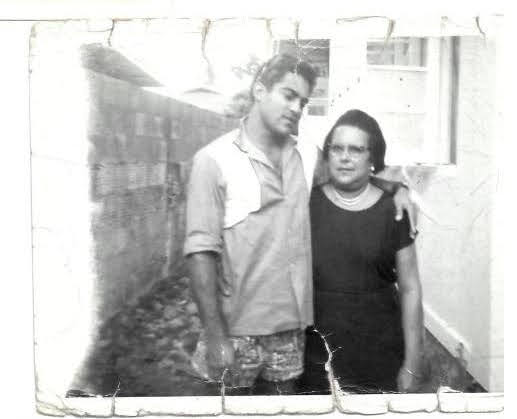

His father was an unsuccessful car salesman, the son of a rural Brahmin priest who had emigrated from India. His mother was a sales assistant in a Department store, a Creole of part-Scottish-part-African stock.

Rejected by both families for marrying beneath or outside their cultural group, his parents settled in a racially and socially diverse neighbourhood, originally settled by freed slaves, in Belmont, Port of Spain.

Mustapha’s childhood was spent playing ‘boy’ games, exploring the nearby forest and backyards of the tightly-packed houses, unconsciously observing and absorbing the personal lives of his neighbours. His first school was a wooden room on stilts on the top of a hill, its sole teacher a tall, elegant black lady, who was well liked and respected for her ability and no-nonsense manner.

TEENAGE

In his pre-teens he discovered a love of the cinema. Going to double features sometimes twice a day, he would describe films by acting the parts, and with the bags of rice and sugar of a next-door shop serving as mountains, produced and directed his own Western scenarios with himself and the owners’ children as the cast. His own character was invariably the outlaw Black Bart. In Mustapha’s boyish version, crime paid; Bart always got away with the robbery, and returned to the cave of cardboard boxes he had built under the house. At length the child playing the Sheriff complained, “How come he always get away? Dat don’t happen in de flims.”

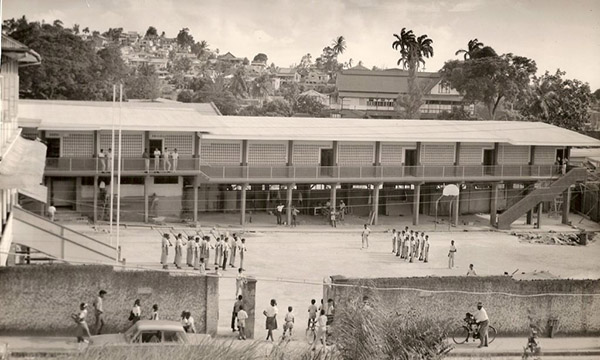

EDUCATION

His education at a local secondary Boys school was fitful, but uneventful. Uninspired, and disliked by teachers for being a lazy wastrel, he became a solitary subversive, and after breaking a school rule that decreed “no rubber band and bent pin battles on last day of school,” he collected six strokes from a police cane. He doesn’t remember whether or not he cried, but at last he made his escape. His father’s death served as his pretext.

EMPLOYMENT

His first employment – and his first exposure to grownup office politics, co-workers’ personal lives, and the world of work — was as an office boy in a solicitor’s office. The job lasted for five years, and the most valued advantage he gained from it was a deep appreciation for the English language. It ended abruptly when he was sacked for incompetence, having absent-mindedly left the weekly office wage package in the foyer of a client’s office. By this time his curiosity about life in the outside world, and his plans for the future and a career were coming into focus. Influenced by Playboy magazine and his idol at the time, James Dean, he would to go to the USA and study acting. Unfortunately, the money he had carefully saved to pay for travel and fees was confiscated to reimburse the lost wages.

Mustapha got a job supervising the stock at the bar of a smart French hotel in Port of Spain, and began saving to go to London. There he believed he could express himself more freely than was possible in what he perceived as the narrow-minded, oppressive society he had grown up in. He’d be an Artist, a Writer, something creative. Meanwhile he and the barmen practiced creativity in scamming the accounts, and he was eventually sacked for lack of industry. Once again he escaped – this time from a threatened marriage. The political and emotional entanglements of the staff and guests at the hotel inspired his play Independence.

During periods of unemployment Mustapha became a voracious reader of European “classical” literature, and his curriculum – haphazard, rudderless, chaotic though it was – set him on his way toward the fulfillment of his dream. The style and power of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar probably determined the medium he would choose.

Whilst working at his next job as a tally clerk on the wharves, he noticed a book being passed around furtively among his fellow workers. When he enquired, he was told to put his name on a waiting list; it was From Superman to Man by J. A. Rogers, and it also had a profound influence on him – his first look at African-American history, and the context of his own experience on the wharves, when.he was accused of being an informer, and he lived and worked in constant fear of personal attack for weeks, until the real informer was discovered, and revealed to be a carpenter and part-time preacher, ironically named Righteous.

Read on to learn more about Mustapha’s life after he arrived in London.